The unofficial ambassador of Signal Hill National Historic Site is basking in the late summer sun and being fawned over by strangers. He’s getting pats galore, and even some hugs and kisses, while while posing for too many photos to count.

What’s his name? Sable Chief.

How old is he? Seventeen months.

How much does he weigh? About 135 or 140 pounds, but he should grow to 175.

Mount Pearl retiree Ed Jackman likes to bring his Newfoundland dog, Sable Chief, to Signal Hill National Historic Site most days. Sometimes he brushes him up here so the wind will blow the hair away/Jennifer Bain

Sable Chief — the “Signal Hill Dog” — is doing his breed proud serving as a symbol of Newfoundland and Labrador and showcasing his gentle temperament since his strong swimming skills and bravery aren’t needed for this particular gig.

His owner Ed Jackman sits beside him on a bench between the parking lot and the iconic Cabot Tower under the “kilometre sign” that shows the distance from here in St. John’s to a dozen global cities.

“You can see the smiles he puts on people’s faces — how happy they are,” says Jackman. “It’s good for my mental health, too, coming up here, having my coffee and answering questions.”

A Newfoundland dog named Sable Chief was the mascot of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment in World War I. His taxidermied body is on display at the Rooms in St. John’s/Jennifer Bain

To be clear, Sable and Jackman don’t work for Parks Canada or even officially volunteer here. Jackman is a retired provincial government employee who served as a welfare officer for shelters. After spending his career with people who were miserable and facing tough times, it’s nice to do “something relaxing and something that brings people happiness for a change.” Jackman lives in suburban Mount Pearl and has been bringing his Newfoundland dogs to Signal Hill since about 2006.

Schooner was first because he was a show dog who needed to be socialized. Chieftain (Chief) was next, and after eight years, was very well known. The dog that was named for an Irish folk band loved the attention but sadly died in 2022. Sable Chief (Sable for short) comes from the same breeder and debuted here last year as a puppy. “He’s probably the calmest we’ve had at this age,” admits Jackman, who comes to Signal Hill whenever he can, loosely from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. As my taxi driver puts it: “He’s a fixture up there — him and his dog. He’s like a tourist attraction.”

Sable Chief, if you probe beyond the top three questions, is the name of the famous mascot of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment in World War I who was killed in a truck accident in 1919. Do stop by the Rooms, the province’s largest public cultural space, to see his taxidermied remains.

Parks Canada’s Mindy Clements, a visitor facilities attendant, always takes a moment to say hello to Sable Chief/Jennifer Bain

Intelligent, loyal and sweet. Those three words best describe Newfoundland dogs who, along with Labrador retrievers, are recognized as an essential part of the province’s historical and cultural heritage. Sable’s ancestors were once used on fishing vessels to haul nets and retrieve people and objects from the water. On land, they pulled milk and mail wagons and were hitched to carts loaded with fish.

“Hello pretty fella,” one woman enthuses at the sight of Sable.

“He’s just chill, eh?” a man notes.

“Thank you for having him here today,” says another woman. “No problem,” Jackman replies.

Signal Hill National Historic Site, and Cabot Tower, loom over downtown St. John’s/Jennifer Bain

I’m not actually here just to pat a dog — it’s a bonus. Whenever I’m passing through town, I come for what’s touted as Canada’s most intense and picturesque city hike.

The North Head Trail is just one mile long, but oh what an experience it is with astounding views of the North Atlantic and St. John’s Harbour.

There’s nearly 500 feet of elevation and 100-plus wooden stairs. I hike from top to bottom but runners and those seeking cardio challenges do it the harder way with Cabot Tower (and maybe Sable Chief) waiting at the top as a reward.

A view of the North Atlantic Ocean in August from Signal Hill’s North Head Trail/Jennifer Bain

“It’s a great viewing place for whales but particularly for icebergs when they come down,” notes Glenn Keogh, Signal Hill’s manager of national historic sites and visitor experience.

Some kind of footpath along the Narrows — the entrance to St. John’s Harbour — to the “north head” of this peninsula has reportedly been in use since the 1500s. About 80,000 people now hike this trail each year when they come to one of Canada’s most iconic, treasured and visited historic sites.

Signal Hill actually draws about 750,000 visitors a year and was vitally important to Canada’s defence and communications history.

Cabot Tower, named for explorer John Cabot, is the crown jewel of Signal Hill/Jennifer Bain

It protected St. John’s from military attack from the 1640s to the Second World War. Flags once announced the arrival of ships — everything from small fishing boats and large naval fleets to merchant ships — while gun batteries offered protection from warships, invading armies and Nazi submarines.

As Parks Canada puts it, this is where “soldiers stood guard against invaders, where flags signaled news of approaching ships and where a single letter `S,’ sent from across the ocean, landed here, at this site, and announced a worldwide revolution in communications.” (Guglielmo Marconi received the world’s first wireless signal here in 1901.)

The crown jewel is Cabot Tower, which served as a flag-signaling tower from 1900 to 1958 and commemorates Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee and the 400th anniversary of Italian navigator/explorer John Cabot’s voyage across the Atlantic to the New World.

It can get windy on Signal Hill’s North Head Trail, as writer Jennifer Bain discovers/Jennifer Bain

But I come to this 262-acre site on the Signal Hill Peninsula more for the free hiking than the history.

“(Signal Hill) is truly a world apart, providing visitors with spectacular hiking experiences atop exposed ocean headlands, along centuries-old footpaths, and through forested areas,” is how the site’s 2018 management plan describes it. “Given the breadth and variety of its natural landscapes, (it) offers an authentic `park’ experience in an urban setting.”

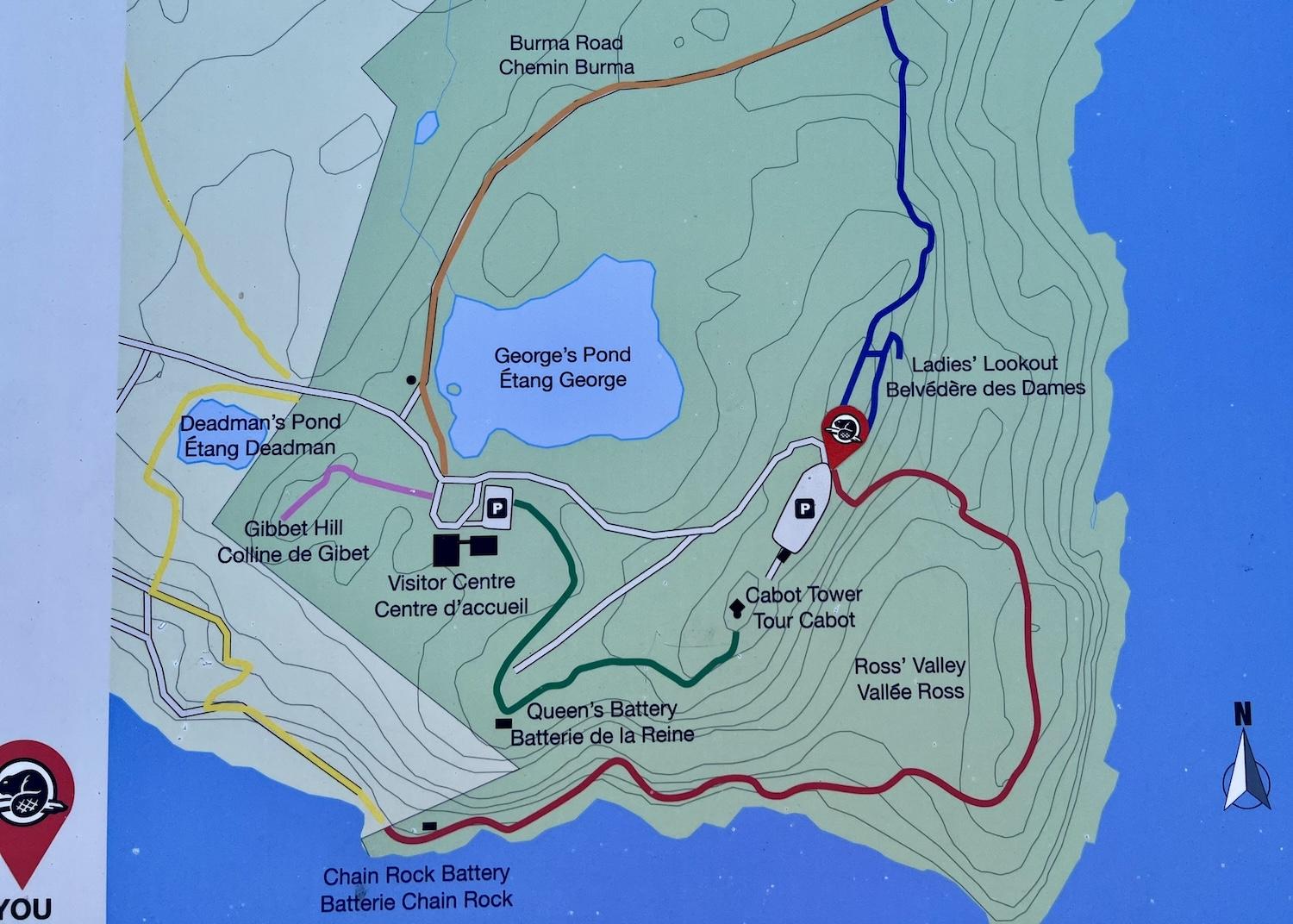

Keogh loves Ladies Lookout Trail, the site’s highest point where flag signals were once flown and where there is currently an eagle’s nest. It connects to the Burma Road Trail, which goes between Cuckold’s Cove and George’s Pond (Newfoundland slang for a small body of fresh water) and then connects to the 0.2-mile Gibbet Hill Trail.

From North Head Trail, a view into St. John’s Harbour to a cruise ship and downtown/Jennifer Bain

Let an interpretation sign reveal how gibbetting involved dipping the bodies of executed criminals in hot tar, encasing them in an iron cage and chains, and hanging them on public display until they rotted to discourage would-be criminals and “comfort” the victims’ loved ones.

“It was a fairly gruesome way of trying to keep law and order in the city,” admits Keogh. The gibbet that was here from the 1750s to about 1795 was likely only used a few times.

Another short trail — Centre to Summit — links the visitor center with Cabot Tower. Then you’re back at the upper parking lot where you can tackle North Head, the longest and most popular trail.

Signal Hill’s trails are short, easy to follow and minutes from downtown St. John’s/Jennifer Bain

Parks Canada doesn’t offer guided hikes, but there’s a map at the trailhead and it’s impossible to get lost.

“Caution! Watch for falling rocks.”

“Attention! Dangerous cliff. Stay on designated trails.”

“Caution. Sections of trail are dangerous due to steep cliffs and narrow paths. Care should be taken particularly with small children.”

You’ve been warned.

As tempting as it is, you’re not supposed to go off North Head Trail and get too close to the ocean/Jennifer Bain

“The trail poses a bit of danger for people not used to the coastline,” Keogh acknowledges. “But it’s not like Cape Spear National Historic Site where we’ve had a number of people over the years swept out, and where the waves are unpredictable and it’s very difficult to retrieve people without search and rescue vessels.” Just days after we speak, a man unfortunately falls into a chasm along North Head Trail and dies as the city catches the edge of Hurricane Ernesto.

Mindful of the danger of slipping on wet rocks, I save my hikes for sunny days. Some people only go part way down North Head Trail and then return to the parking lot.

Starting from the top, not far from where Sable Chief greets his fans, you’ll make your way down wooden stairs (which are slated for an upgrade) into Ross’ Valley. This steep part of the journey is apparently like walking down the equivalent of 20 storeys.

On North Head Trail, the Cabot Tower looms above Ross’ Valley/Jennifer Bain

This “hanging valley” was formed by a glacier during the last ice age. It was once home to gardens (so look closely to see potato drills/mounds) and a small quarantine hospital called Prowse’s Folly.

As Keogh explains, Signal Hill has housed two hospitals, a larger one set back from the sea and a smaller one closer to the coastline for people who arrived by ship with communicable diseases like cholera.

The bigger one was first constructed as two-storey barracks and later used as a prison and quarantine hospital where people were treated for diphtheria, smallpox and tuberculosis. It was in a vacant room of this hospital that Marconi received the first transatlantic wireless signal.

Two of Parks Canada “red chairs” on North Head Trail face the ocean and Cuckold’s Cove. The federal agency encourages people to take photos for social media and tag them #ShareTheChair/Jennifer Bain

Back to the trail, you’ll soon spot the first of two sets of Parks Canada’s red Adirondack chairs. These look towards Cuckold’s Cove and are apparently near some fox dens. Another set at the tip of North Head, facing South Head and the Fort Amherst heritage lighthouse, was removed.

“It gets pretty gusty down in that area,” says Keogh.

It’s not far to a second set of red chairs that are great for cruise ship watching and admiring the colorful buildings downtown. Soaring over the skyline is the Rooms, clad in glass, granite, aluminum and wood with peaked red roofs.

One treacherous and narrow part of North Head Trail has a safety chain bolted to the rocks/Jennifer Bain

From here, things get challenging. The trail narrows and at one point you have to cling to a safety chain bolted to the rocks.

Back in the 1660s, fishermen placed cannons here and on the opposite side of the Narrows, augmented by a cable (likely made of rope) to keep enemy ships from entering the harbor. The area became known as Chain Rock Battery because of the large rock just off the shore to which booms and chains were anchored as the English and French fought for control.

The battery was abandoned for a spell and then in the Second World War, Canadian forces built a new emplacement here called Fort Chain Rock. There was a wire anti-submarine net between Chain Rock and Pancake Rock before three pairs of anti-torpedo baffles were suspended in the Narrows in 1941 and then supplemented by an anti-submarine net two years later.

It would be nice to have signage explaining the significance of this abandoned bunker on North Head Trail/Jennifer Bain

“We have lots of signs — some people say too many signs,” says Keogh. But I disagree. I had to cobble together this history of North Head Trail from various signs across the site and from its website.

Anyway, I love the trail’s grand finale.

First you’ll pass an abandoned concrete bunker that likely held a Second World War cannon. Then you’ll see a chain link fence over houses in the Lower Battery neighborhood that Parks Canada maintains to prevent rockfalls.

Nicola Blazier nears the end of North Head Trail where it crosses from Parks Canada land into the colorful Battery neighborhood of St. John’s/Jennifer Bain

Finally, you’ll cross a wooden deck that feels like it belongs to the house it’s in front of but is actually Parks Canada property. A reassuring sign says “public exit” and Keogh tells me the deck was built in consultation with a previous homeowner.

You’ll wind up on Outer Battery Road and can either make your way downtown or take the Grand Concourse Connecting Trail back up Signal Hill if you’ve parked there, and where Jackman and Sable Chief may or may not be waiting.

To get on or off Signal Hill’s North Head Trail, you’ll have to cross this Parks Canada deck attached to a private home/Jennifer Bain