“SPECIAL,” read the pink card tucked into the archival box with JODA 17384.

It was a National Park Service warning for anybody handling this mandarin-sized chunk of greenish brown rock embedded at one end with what looked like creamy Tic Tacs.

“The tag tells people this is a unique specimen and not to break it,” Nicholas Famoso, paleontology program manager and museum curator at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, explained as he showed it off from the safety of its archival box. “It’s 29 million years old.”

Nicholas Famoso, a palaeontologist at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, cradles a fossilized grasshopper egg pod/Jennifer Bain

The Oregon park captured headlines in January when a study published in the journal Parks Stewardship Forum revealed this unusual object was a fossilized grasshopper egg pod containing about 50 eggs.

On a road trip through the state in September, I wrangled a behind-the-scenes tour of the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center and Visitor Center just weeks before the park put the celebrated fossil on display.

This story actually starts in July 2012 when collections manager Christopher Schierup picked up the nest during a routine visual survey of an undisclosed part of the Sheep Rock Unit’s Blue Basin area and wrapped it in toilet paper. The paleontology team has found almost 150 individual eggs or egg groupings since the 1990s and suspected they came from ants, so the new object was shelved in the accession storage room until Famoso joined the team.

The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center and Visitor Center is in the Sheep Rock Unit of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument/Jennifer Bain

Schierup flagged it to him in 2016 and it was quickly catalogued and put in the collections. But it languished again until Famoso read a paper describing modern insect eggs, took measurements and realized the find was likely related to grasshoppers.

With University of California, Berkley doctoral student Jaemin Lee researching the mystery, and micro-CT scans conducted at the University of Oregon by Angela Lin, the trio eventually proved the nest pod was indeed made by an ancient grasshopper.

They were delighted by unexpected interest in their 75-page study.

Palaeontologist Nicholas Famoso stands in the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center near the public viewing window into the research lab/Jennifer Bain

“A lot of people are creeped out by bugs,” Famoso acknowledged. “One of the most common things that I heard, once this got out on social media, was `Oh my god, don’t hatch them’ and `Oh no, now they’re going to create genetically engineered Jurassic Park bugs.’ And I’m like, that’s not how science works. Can these things hatch and come back? The answer is no. There is no organic material whatsoever.”

On the other hand, the fossil find was easy to understand. People know what grasshoppers are and got a kick out of discovering they lay eggs underground. Meanwhile, the scientists loved knowing this was the world’s first confirmed subterranean grasshopper nest.

For a spell, Famoso had one of two keys to the secure cabinet where JODA 17384 was stored in the paleontology center named for the man who first identified the region as a world-class paleontological site and became Oregon’s first state geologist.

At the Clarno Unit, a gentle reminder that national park rules apply/Jennifer Bain

Established in 1975, John Day Fossil Beds is a “living laboratory” where visitors can discover science in action and explore the world of long-gone plants and animals. The area was named by Condon for a man who was robbed by a nearby river while on an overland expedition to the Pacific Fur Co. post in Astoria in 1812. What’s now called the John Day River boasts eroding and exposing fossil-bearing rock layers.

Fossils, the Park Service explains, are evidence of life that has been preserved by natural processes in the earth’s rock layers. They can be as tiny as a cell or as large as a coral reef. Sabre-toothed nimravids, three-toed horses and “sheep-pig-camel-like” oreodonts once roamed this particular landscape.

The 14,000-acre national monument in east central Oregon has three units, each about an hour apart. Since there’s no park lodging or camping, I stayed at the Painted Hills Vacation Cottages & Retreat in Mitchell.

Stunning views from the Painted Hills Overlook in John Day Fossil Beds National Monument/Jennifer Bain

That positioned me to enjoy sunset at the nearby Painted Hills Unit, gawking at color-splashed hills and popcorn-textured claystones, hiking four of the five short trails in rapid succession, and photographing the scene at the golden hour.

It’s a bit of a drive to the remote Clarno Unit, which is home to two off-limits fossil sites.

When I took the Geologic Time Trail from the parking lot/picnic area, each step represented 37,000 years travel back in time. “Signs along this trail use the scientific notations for time,” interpretive signs explained, “Ka (Kilo annum, or a thousand years) and Ma (Mega annum, or a million years).”

Look for this fossil-covered rock on the short Trail of the Fossils in the Clarno Unit/Jennifer Bain

That trail connects to the even shorter Trail of the Fossils, where you can see leaf fossils embedded in a giant rock. I also marveled at craggy cliffs called the Palisades that formed when volcanic, ash-laden mudflows swept through a forested landscape about 45 million years ago. The cliffs are reportedly filled with fossils, but they’re hard for a layperson to pick out so watch for signs of ancient life on fallen boulders instead.

I did climb the short but steep Clarno Arch Trail to see the namesake rock arch plus two fossilized logs, one vertical and one horizontal.

There were no rangers around to provide interpretation, just warning signs that said: “Remember, all fossils, rocks, artifacts, plants, animals, and other natural and cultural features in the park are protected by Federal law. Do not collect, dig, or disturb them.”

Hiking the Island in Time trail in Blue Basin in the Sheep Rock Unit is a feast for the eyes/Jennifer Bain

The Sheep Rock Unit is the busiest.

Taking Famoso’s advice, I hiked Blue Basin’s Island in Time trail through colorful banded badlands instead of the longer Blue Basin Overlook trail above them.

Colorful interpretive signs provided visuals of the creatures that once roamed here. Three plexi-bubbles with replica casts helped bring tortoises, oreodonts and saber-toothed nimravids to life.

On Blue Basin’s Island in Time Trail, a plexi-bubble and interpretive signage teach about oreodonts/Jennifer Bain

This unit has the Cant Ranch Historic District (which was beside a staging area for wildfire operations) and the visitor center, which doubles as a research facility. Before exploring the fossil museum gallery, peer through picture windows into the laboratory and collections room. “We try to have somebody in the window on days the visitor center is open,” said Famoso.

The day I visited, lab manager Jennifer Cavin was hosting a film crew. She had tidied up the lab but I still saw replicas of a rhino skull, clam shell and entelodont (aka hell/terminator pig) skull.

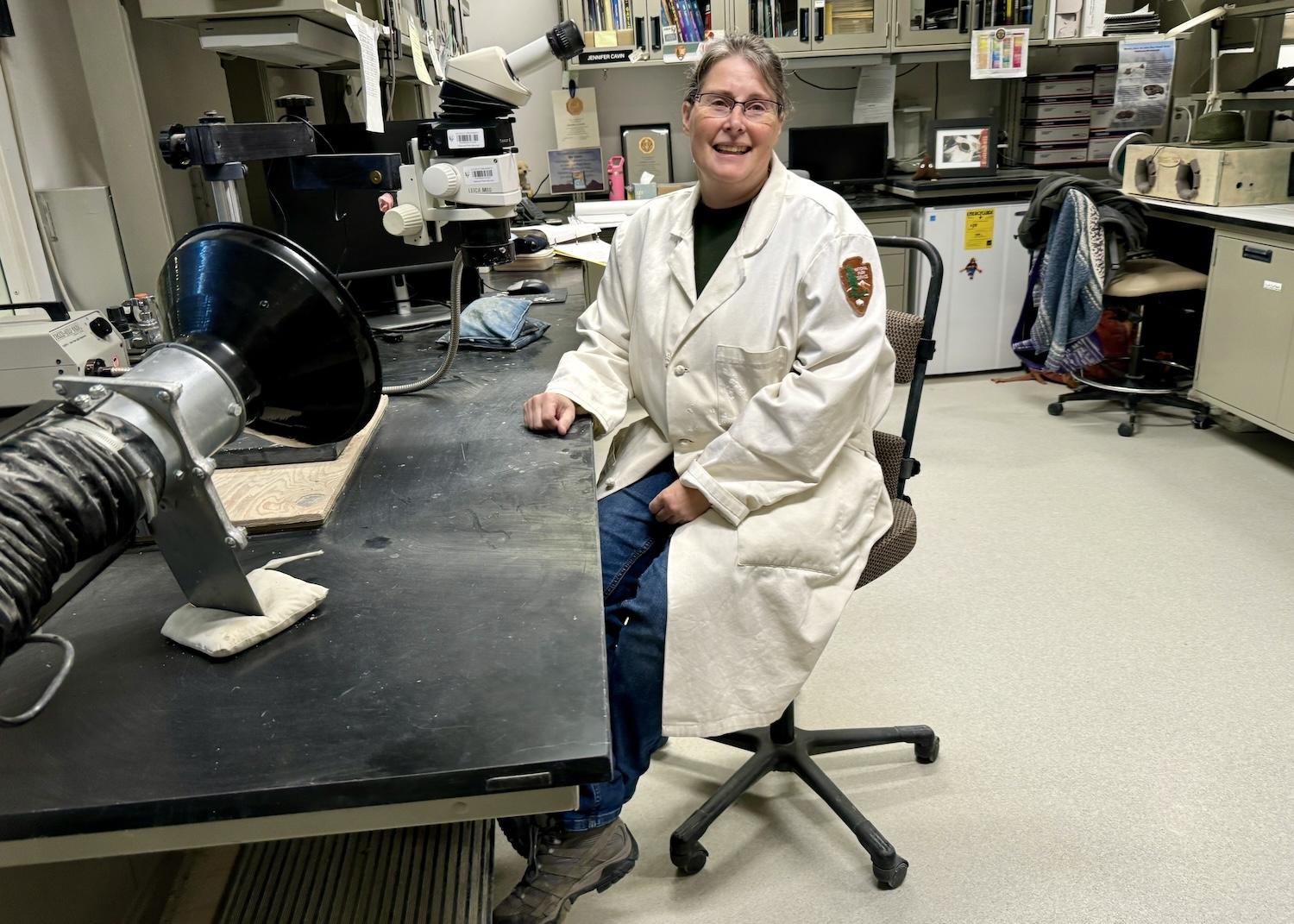

Jennifer Cavin is the lab manager and fossil preparator at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument/Jennifer Bain

John Day Fossil Beds talks about a lot of geologic time.

The oldest rocks that it tells the story of are about 55 million years old and the youngest are between seven and five million years old. “One of the spectacular things about this monument is that we have, I think, the longest record of time within the age of mammals of anywhere within the national park system,” Famoso pointed out. “And that’s kind of our claim to fame.”

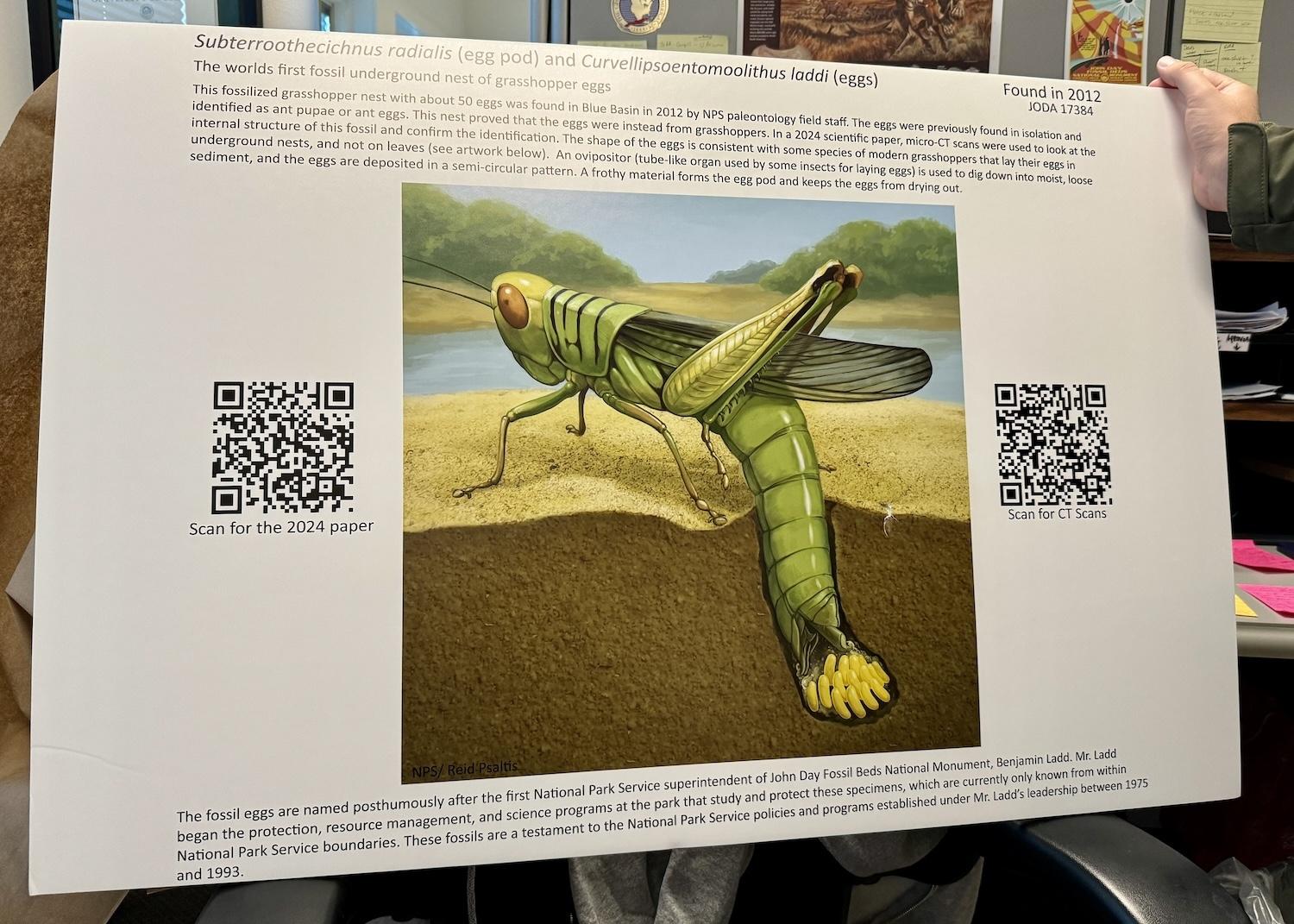

In his office, I got a sneak peek of a new exhibit panel for the grasshopper egg pod. It had arrived from the printer four times bigger than expected and damaged so a replacement was being ordered.

A smaller version of this panel is now on display at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument’s visitor center/Jennifer Bain

In paleontology, the descriptive naming protocol for animals and plants can also be used for eggs and so this pod is now Subterroothecichnus radialis (egg pod) Curvellipsoentomoolithus laddi (eggs). The species is named for the park’s first superintendent, the late Benjamin Ladd.

“He was going out right after we became a national monument, cruising around to remind people that this wasn’t a state park anymore and that they couldn’t legally collect fossils here anymore,” said Famoso. “He did a lot of work to help make sure that the fossils in this area were protected.”

The paleontologist worked with California artist Reid Psaltis to come up with an image of the grasshopper, which was inspired by rice grasshoppers and is seen by water and woods. Remember— no body fossils have yet been found.

Benjamin Ladd, left, was the first superintendent of John Day Fossil Beds. The fossilized grasshopper find was named in his honor/Jennifer Bain

“It’s a hypothesis of what we think this animal might have looked like — we don’t know if we’re right, we don’t know if we’re wrong,” admitted Famoso. “That’s the great thing about it — it’s an untestable hypothesis and so you have a lot more freedom with those sorts of things to allow the artist to do what they feel is within their range.”

The image shows a rather adorable green and gold grasshopper starting to lay eggs in a hole in the moist, loose ground, some darkening as they age and others surrounded by frothy material that forms the egg pod.

Visitors can scan a QR code to see the micro-CT scans of the nest and read the paper (“Microtomography of an enigmatic fossil egg clutch from the Oligocene John Day Formation, Oregon, USA, reveals an exquisitely preserved 29-million-year-old fossil grasshopper ootheca”).

As of mid-October, the fossilized grasshopper egg pod is on display at the John Day Fossil Beds visitor center/Nicholas Famoso, NPS

About a month after my visit, JODA 17384 was taken out of the locked “type cabinet” and removed from its archival box, where it was cushioned by black and white Ethafoam.

It’s now displayed in the exhibit hall’s “Discoveries” case in the spot long held by the upper arm bone of the park’s largest sabre-tooth. It sits on a museum exhibit pedestal on foam specially cut to keep it in place and on black plastic that resembles gravel.

“We want to make sure that we have these things as protected as possible while still allowing people to be able to see them,” Famoso explained. “So it gets locked up every night. There’s minimal light exposure. There’s as much control over temperature as we can get in this space. We will try to keep it as stable as we can.”

The nest pod is too fragile to be subjected to molding and casting, so when it’s eventually time for it to go back into storage and make way for a newer find, something like a 3D print could take its place in the museum.

Spot the live grasshopper in the bottom right corner of this photo on a Blue Basin trail/Jennifer Bain

All that fossil grasshopper talk made me long to see a live grasshopper — after expressing remorse for all the ones I caught for fishing bait as a kid.

“Grasshoppers are pretty ubiquitous and a lot of places in the world use them as food,” mused Famoso. “The only protections that grasshoppers in the monument have are the protections that all wildlife in the national monument have. So you’re not allowed to take them, not allowed to do anything like that with them, but other than that, once they jump one inch out of the monument, fair game.”

Hiking in Blue Basin, in the same general vicinity where Subterroothecichnus radialis Curvellipsoentomoolithus laddi was found one summer’s day a dozen years ago, a single grasshopper appeared. I hoped to catch it in the act of laying eggs, but instead simply watched it blend in with the gravel oblivious to its protected status and the buzz surrounding its fossilized ancestor.

Inside the fossil prep lab at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument/Jennifer Bain