It was a reminder of Christmases past, a time when simplicity not splashiness ruled.

The Halifax Citadel National Historic Site was decorated with unadorned balsam fir trees and wreaths dolled up only with red bows. The main drink being served that late November night was hot chocolate (unless you partook in an extra tasting of spirits).

We carried electric lanterns around the restored 19th-century British fortification in Nova Scotia. We cheered as our 78th Highlander guide treated us to a magic lantern show using a vintage ancestor to modern slide projectors. And when Father Christmas burst through the heavy wooden door into the barracks, he wasn’t lugging a sack of consumer goods, just a tin of so-called sugar plums.

Father Christmas greets guests on the Citadel by Candlelight Holiday Tour in late November/Jennifer Bain

“Back in the Victorian days when the 78th Highlanders were celebrating in this room right here, I would crash right in at any old time at every single Christmas party,” he explained. “What would happen is, everybody would be enjoying a Christmas party and one of the soldiers would say `Oh is that the time? I have to go do something,’ and he’d leave the party. He wouldn’t come back, but who would come back would be me — Father Christmas.”

As the embodiment of Christmas, he was tasked with ensuring a good time was had by all.

“The most important job that I had back in the Victorian days was I was the guy who delivered the sugar plums to the party, because that’s probably the most important part of Christmas,” said Father Christmas.”You ever hear of children on Christmas Eve with visions of sugar plums dancing in their heads? Could you imagine how horrible it would be to have to spend a single Christmas without eating at least one juicy sugar plum?”

Snow hadn’t fallen for this Nov. 30 candlelight tour of the Halifax Citadel, but there were Nova Scotia balsam fir trees and wreaths to be seen/Jennifer Bain

Only one person on our Citadel by Candlelight Holiday Tour had ever tried a sugar plum. But apparently the 78th Highlanders Regiment of Foot — a British Army unit that was stationed in Halifax from 1869 to 1871 — once enjoyed the hard candy version named for its shape not its main ingredient or flavor.

“Any last minute requests?” Father Christmas asked before posing for photos with a hearty ho-ho-ho.

“I think we all want a sugar plum,” one woman said sweetly.

“Just because you asked, I will give you and you alone a sugar plum and you have to tell everyone else in the room how good it tasted,” Father Christmas teased.

When the Halifax Citadel was an active garrison, Christmas decorations and festivities were simple but important for morale/Jennifer Bain

“The thing I would like is for everyone else to have one, too,” her quick-thinking companion interjected.

“I like that idea — giving and generosity,” Father Christmas mused. “Well I just happen to have sugar plums right here. These are actually sugar plums and they are very hard to find.”

With a flourish, he gave us each small paper bags with just a few ordinary hard candies standing in as sugar plums. He made sure to include Kiana Sokolic, a military interpreter from the non-profit Halifax Citadel Society who was dressed as a colonel while regaling us with 75 minutes worth of Christmas stories.

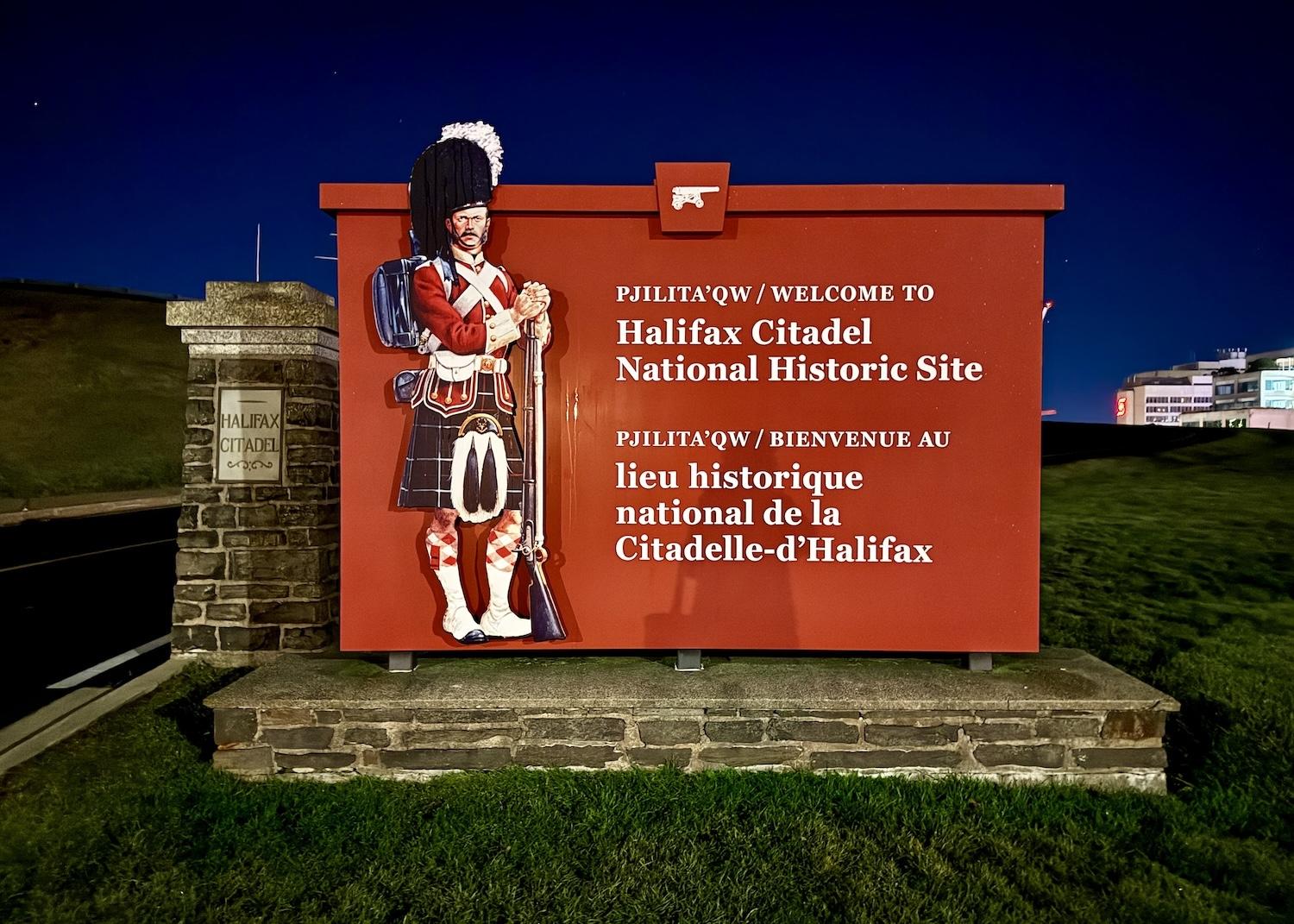

Halifax Citadel National Historic Site looms over downtown Halifax in Nova Scotia/Jennifer Bain

The Citadel, a strategic hilltop with commanding views of Halifax Harbour, immerses people in the city’s social and military history and is one of five sites that make up the Halifax Defence Complex. It served as soldier barracks and a command centre for Halifax Harbour defences during World War I, and a temporary barracks for World War II troops. The star-shaped stone fortress is now beloved by cruise shippers, visitors and locals alike.

“I always launch my personal Christmas with our Victorian Christmas event — that’s when the season starts for me now,” Hal Thompson, Parks Canada’s visitor experience product development officer for the site, told me.

“It sounds silly, but there really is a Christmas spirit. Everybody’s really happy. Everybody really loves that event. Everything we do is fun. The stories we’re telling are very positive, they’re not negative. We’re not talking about war and that sort of thing. We’re talking about how people lived and how they tried to celebrate. And it’s also about the evolution of our own modern Christmas, and the commercialization that started too, so there’s that bit of negativity, I suppose. But it just has a great feeling to it.”

At Halifax Citadel National Historic Site, military interpreter Kiana Sokolic with the Halifax Citadel Society is joined by Parks Canada’s Hal Thompson during the Raise Your Holiday Spirits tour and tasting/Jennifer Bain

I had just missed weekend-long Victorian Christmas festivities. Two Victorian holiday recipes on the Citadel’s website didn’t cut it as a consolation prize. Neither did online instructions for three Victorian holiday crafts. Luckily, there was still time to join the Citadel by Candlelight Holiday Tour and the Raise Your Holiday Spirits tour.

Sokolic led both tours and spoke about how alcohol raised everybody’s spirits back in the day. We had a private sampling of three spirits crafted by Compass Distillers for the society and aged right here. Their names — Noon Day Gin, Daily Ration Rum and Fort George Genever — helped tell important stories as we drank in a recreated coffee bar and soldier’s library.

On the public tour that followed, seven of us were treated to even wilder tales of booze-fuelled shenanigans, that Magic Lantern show with vintage hand-painted Christmas slides, and that moment with Father Christmas.

A vintage Magic Lantern projects a Christmas story during an evening tour of the Halifax Citadel/Jennifer Bain

The Halifax Citadel has offered candlelight tours off and on for decades, including a popular ghost-themed version that Thompson collected stories for.

“The point of it is that not everybody’s interested in an old fort,” he conceded. “Once you get them up here and you tell them the stories, they’ll go `Oh, that’s interesting.’ They might not want to come up to an old fort, but they might be interested in folklore so we present it as a folklore tour instead of a ghost tour. Some of the stories are old, some are more recent, but we also slip the history in there while they’re on the tour.”

This was the second year for holiday candlelight tours. Most of Canada’s national historic sites are seasonal, but the city-based Citadel’s grounds stay open year-round and it fires a daily noon day gun. Still, its visitor center, exhibits and public tours mainly run from May to November.

Christmas decorations like this wreath are kept deliberately simple at the Halifax Citadel/Jennifer Bain

“One of the unbroken uses of this site when it was an active military base is that people did things up here, there were functions up here — parades and sporting events and parties and you know what,” explained Thompson. “That really hasn’t changed. It was transferred to Parks Canada in 1952 but a lot of the actual uses of the people of Halifax for Citadel Hill, as they would refer to it instead of saying national historic site, haven’t changed.”

He hopes to one day see the Citadel fully open year-round, but for now he’s happy with the bonus Christmas season offerings.

An eight-point star lights up Cabot Tower at Signal Hill National Historic Site each year in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador/Parks Canada

So how did Parks Canada celebrate Christmas this year?

On Cape Breton Island, the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site had a dinner concert series. A giant eight-point star was lit on Cabot Tower at Signal Hill National Historic Site in Newfoundland and Labrador. Ontario’s Fort George National Historic Site had a “Great Taste of Canada Experience” with Indigenous cuisine while fictional heroine Anne of Green Gables visited Green Gables Heritage Place festivities in Prince Edward Island. The Banff Winter Carnival kicked off at Cave and Basin National Historic Site in Alberta.

Danny Cram, the charismatic blacksmith who I met earlier this year at Fort Langley National Historic Site in British Columbia, helped people make copper lanterns and copper stars. Manitobans harvested Christmas trees from Prince Albert National Park to help maintain the Waskesiu Community Fuel Break. (Removing highly flammable coniferous trees creates a “green belt” around the community that’s designed to slow approaching wildfires and give people time to evacuate.)

Parks Canada’s Hal Thompson shows off one of the undecorated fir trees on display at the Halifax Citadel during the Christmas season/Jennifer Bain

Here in Nova Scotia — where Lunenburg County is called the “Balsam Fir Christmas Tree Capital of the World” — growers ship more than 350,000 Christmas trees across North America. Nova Scotia balsam has become the smell of Christmas and it’s something I got whiffs of from trees and wreaths along my candlelight tour of the Citadel.

“Looking at accounts of the garrison from the 1850s, 60s, 70s, the use of just plain fir boughs and fir trees for decoration seemed to be common, so we decided to put some out,” Thompson explained. “Probably the giant outdoor Christmas tree like you see today at (New York’s) Times Square was not quite that common yet, but they might have used plain fir trees in pots.”

When this place was a garrison, it could only be decorated on Dec. 25. The men hung flags and made stars by tying together bayonets and hanging them from the ceiling. They pooled their money for a feast and chipped in for big glasses of hard liquor to give the officers that made the rounds of the barracks offering well wishes.

A guided tasting of three Citadel-aged spirits comes with charcuterie and a festive orange/Jennifer Bain

Besides getting their superiors drunk, the men loved being stationed here in the seaside land of fir trees because merchant ships came loaded with Caribbean rum and one of the most prized of Christmas treats.

“Oranges,” said Sokolic. “It was a very, very special treat because you’re not getting a lot of fresh fruit at that time of year.”

As I peeled one while tasting that trio of spirits, I realized I’d never given much thought to why my parents always placed mandarins wrapped in crinkly green paper in our stockings. Even though I haven’t lived through a world war like they both had, it’s a simple Christmas tradition I’ve passed on to my kids and that will now remind me of that candlelit night I spent at the Halifax Citadel.

A festive chalkboard message at the Halifax Citadel/Jennifer Bain