Editor’s note: Saul Zabar, the elder of the brothers who built Zabar’s from a local Upper West Side grocery shop into an international landmark of whitefish, died on October 7 at 97. Today, we’re republishing this cover story from 1992 about the fractious relationship among the store’s controlling partners.

Murray Klein, one-third owner of the city’s premier delicatessen, picks up his lunch in the busy kitchen of Zabar’s at 11:45 on a weekday morning. In this domain of his, he has a dizzying choice of delectables at hand. But he always eats the same simple meal — an egg white, tuna in water, chopped vegetables, unbuttered bread.

A cook pops the yolk from the egg and hands what’s left to Klein. He gulps it down in two bites. The rest of his lunch is in a brown bag. Just before leaving the kitchen, Klein stops. His green eyes narrow, and his lips curl with anger.

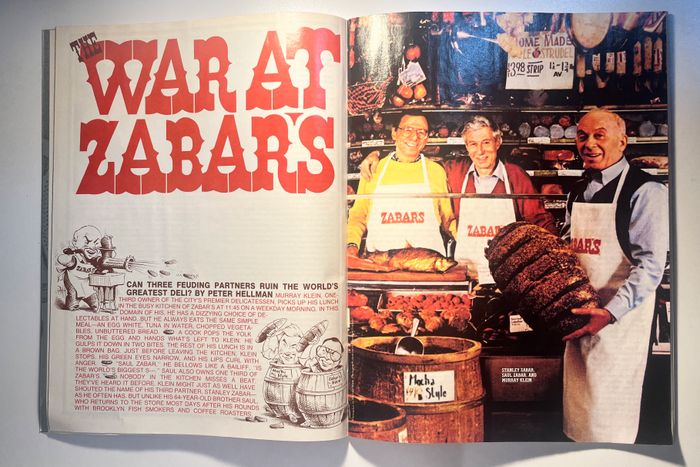

“Saul Zabar,” he bellows like a bailiff, “is the world’s biggest s—.” Saul also owns one-third of Zabar’s. ” Nobody in the kitchen misses a beat. They’ve heard it before. Klein might just as well have shouted the name of his third partner, Stanley Zabar — as he often has. But unlike his 64-year-old brother Saul, who returns to the store most days after his rounds with Brooklyn fish smokers and coffee roasters, 59-year-old Stanley has been absent for months. Perhaps he’s stayed away out of pique over last winter’s forced departure of his son, David, as manager of Zabar’s sanctum sanctorum, its smoked-fish counter.

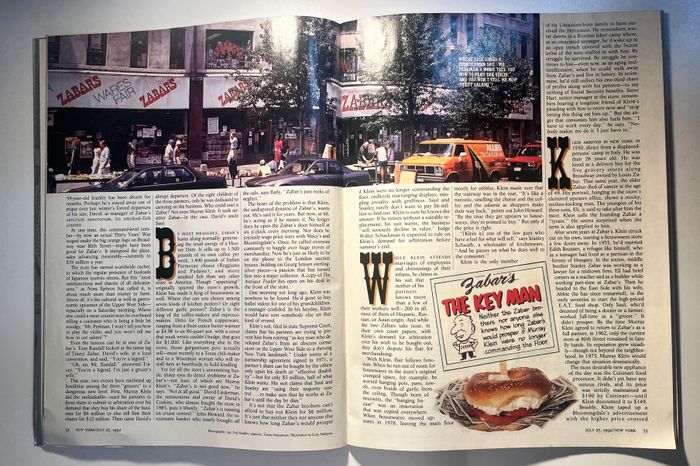

At one time, this command-level combat — by now an actual Thirty Years’ War waged under the big orange logo on Broadway near 80th Street — might have been good for Zabar’s. It energized the place, sales advancing inexorably — currently to $39 million a year.

The store has earned worldwide cachet, to which the regular presence of busloads of Japanese tourists attests. But this “most rambunctious and chaotic of all delicatessens,” as Nora Ephron has called it, is about much more than money or fame. Above all, it’s the cultural as well as gastronomic epicenter of the Upper West Side — especially on a Saturday morning. Where else could a meat counterman be overheard telling a customer who is being a little bit noodgy, “Mr. Perlman, I won’t tell you how to play the violin, and you won’t tell me how to cut salami”?

Even the famous can be in awe of Zabar’s. Tony Randall looked at the name tag of Tracey Zabar, David’s wife, at a food convention, and said, “You’re a legend.”

“Oh, no, Mr. Randall,” answered Tracey. “You’re a legend. I’m just a grocer’s wife.”

This year, two events have ratcheted up hostilities among the three “grocers” to a dangerous new level. First, Murray Klein did the unthinkable — sued his partners to force them to submit to arbitration over his demand that they buy his share of the business for $6 million or else sell him their shares for $12 million. Then came David’s abrupt departure. Of the eight children of the three partners, only he was dedicated to carrying on the business. Who could oust a Zabar? Not even Murray Klein. It took another Zabar — in this case, David’s uncle Saul.

By most measures, Zabar’s hums along normally, generating the retail energy of a Hoover Dam. It sells up to 1,500 pounds of its own coffee per week, 1,400 pounds of Italian Parmesan cheese (Reggiano and Padano), and more smoked fish than any other store in America. Though “appetizing” originally spurred the store’s growth, Klein has made it king of housewares as well. Where else can you choose among seven kinds of kitchen peelers? Or eight different garlic presses? Zabar’s is the king of the coffee-makers and espresso-makers. Ditto for French copperware, ranging from a three-ounce butter warmer at $4.98 to an 80-quart pot, with a cover that weak wrists couldn’t budge, that goes for $1,000. Like everything else in the store, those gargantuan pots actually sell — most recently to a Texas chili-maker and to a Wisconsin woman who will install hers at hearthside to hold kindling.

Seen at right: Stanley Zabar, Saul Zabar, and Murray Klein.

Photo: New York Magazine

Yet for all the store’s unremitting bustle, sharp eyes do detect problems at Zabar’s — not least of which are Murray Klein’s. “Zabar’s is not good now,” he says. “Not at all good.” David Liederman, the restaurateur and owner of David’s Cookies, who almost bought the store in 1985, puts it bluntly: “Zabar’s is running on cruise control.” John Howard, the investment banker who nearly brought off the sale, says flatly, “Zabar’s just reeks of neglect.”

The heart of the problem is that Klein, the undisputed dynamo of Zabar’s, wants out. He’s said it for years. But now, at 68, he’s acting as if he means it. No longer does he open the Zabar’s door himself at six o’clock every morning. Nor does he joyously wage price wars with Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s. Once, he called overseas constantly to haggle over huge troves of merchandise. Now he’s just as likely to be on the phone to the London auction houses, bidding on Georg Jensen sterling-silver pieces — a passion that has turned him into a major collector. A copy of The Antique Trader lies open on his desk in the front of the store.

One morning not long ago, Klein was nowhere to be found. He’d gone to buy ballet videos for one of his grandchildren, a manager confided. In his heyday, Klein would have sent somebody else on that kind of errand.

Klein’s suit, filed in state Supreme Court, claims that his partners are trying to prevent him from retiring “as key man who developed Zabar’s from an obscure corner store on the Upper West Side to a thriving New York landmark.” Under terms of a partnership agreement signed in 1971, a partner’s share can be bought by the others only upon his death or “effective disability” — but for only $3 million, half of what Klein wants. His suit claims that Saul and Stanley are “using their majority control … to make sure that he works at Zabar’s until the day he dies.”

It’s not that the Zabar brothers can’t afford to buy out Klein for $6 million. It’s just that neither they nor anyone else knows how long Zabar’s would prosper if Klein were no longer commanding the floor, endlessly rearranging displays, mingling joviality with gruffness. Saul and Stanley surely don’t want to pay $6 million to find out. Klein is sure he knows the answer: If he retires without a suitable replacement, his suit warns, the business “will seriously decline in value.” Judge Walter Schackman is expected to rule on Klein’s demand for arbitration before summer’s end.

While Klein attends marriages of employees and christenings of their infants, he claims in his suit that neither of his partners knows more than a few of their workers well — 200 in all, most of them of Hispanic, Russian, or Asian origin. And while the two Zabars take issue, in their own court papers, with Klein’s demand for arbitration over his wish to be bought out, they don’t dispute his flair for merchandising.

With Klein, flair follows function. When he ran out of room for housewares in the store’s original cramped space, for example, he started hanging pots, pans, towels, even braids of garlic from the ceiling. Though born of necessity, the “hanging bazaar” was an innovation that was copied everywhere. When housewares moved upstairs in 1978, leaving the main floor mostly for edibles, Klein made sure that the stairway was in the rear. “It’s like a narcotic, smelling the cheese and the coffee and the salamis as shoppers make their way back,” points out John Howard. “By the time they get upstairs to housewares, they’re primed to buy.” But only if the price is right.

“[Klein is] one of the few guys who have a feel for what will sell,” says Stanley Schwalb, a wholesaler of kitchenware. “And he passes on what he does well to the consumer.”

Klein is the only member of his Ukrainian-born family to have survived the Holocaust. He remembers winter dawns in a Russian labor camp where, as an emaciated teenager, he’d wake up in an open trench covered with the frozen urine of the men stuffed in with him. By struggle he survived. By struggle he continues to live even now, as an aging multimillionaire, when he could walk away from Zabar’s and live in luxury. In retirement, he’d still collect his one-third share of profits along with his pension — to say nothing of Social Security benefits. Steve Hart, senior manager at the store, remembers hearing a longtime friend of Klein’s pleading with him to retire now and “stop letting this thing cat him up.” But the anger that consumes him also fuels him. I have to work every day, he says. “Nobody makes me do it. I just have to.”

Klein arrived in New York in 1950, direct from a displaced-persons camp in Italy. He was then 26 vears old. He was hired as a delivery boy for the five grocery stores along Broadway owned by Louis Zabar. That same year, the elder Zabar died of cancer at the age of 49. His portrait, hanging in the store’s cluttered upstairs office, shows a stocky, restless-looking man. The youngest of his three sons, Eli, is said to take after him the most. Klein calls the founding Zabar a “tyrant.” He seems surprised when the term is also applied to him.

After seven years at Zabar’s, Klein struck out on his own, starting a housewares store a few doors away. In 1955, he’d married Edith Bronner, a refugee like himself, who as a teenager had lived as a partisan in the forests of Hungary. In the ’60s, middle brother Stanley Zabar was working as a lawyer for a midtown firm. Eli had brief careers as a teacher and as a builder while working part-time at Zabar’s. Then he headed to the East Side with his wife, Abbie (he has since remarried), in the early ’70s to start the high-priced E.A.T. food shop. Only Saul, who’d dreamed of being a doctor or a farmer, worked full-time as a “grocer.” It didn’t prosper. By the time Murray Klein agreed to retum to Zabar’s as a full partner, in 1962, only the current store at 80th Street remained in family hands. Its reputation grew steadily — though not beyond the neighborhood. In 1975, Murray Klein would change that situation dramatically.

The most desirable new appliance of the day was the Cuisinart food processor. It didn’t yet have any serious rivals, and its price was strictly maintained at $190 by Cuisinart — until Klein discounted it to $149. Brashly, Klein taped up Bloomingdale’s advertisement with the higher price crossed out. Cuisinart stopped selling to Zabar’s.

With speed and stealth, Klein assembled a nationwide network of small retailers who ordered Cuisinarts and resold them to him at a small profit. Only when Klein’s stash of Cuisinarts reached 200 did he announce, on New York’s “Sales & Bargains” page, that he was selling Cuisinarts at $135 — $14 less than he’d charged before Cuisinart had cut off Zabar’s. All 200 sold out in a single day, and Klein gave rain checks for 966 more. It’s hard to believe Klein’s claim that he didn’t lose money in the battle of the Cuisinarts. But it’s indisputable that the publicity for Zabar’s was priceless.

Still, Klein still wasn’t satisfied. After Stanley Zabar read about a Yonkers auto-parts dealer who had won a price-fixing suit against Ford, Zabar’s sued Cuisinart in federal court for restraint of trade. The store was represented by the lawyer from the Yonkers case — a loyal customer of Zabar’s. The case was settled out of court when Cuisinart agreed to sell to Zabar’s free of price controls. (By then, competitive processors had achieved the same result.)

Klein’s next opponent was Macy’s. Determined to draw a higher class of customer to its new gourmet zone, Marketplace in the Cellar — and maybe lure away Zabar’s customers — Macy’s cut the prices of smoked salmon, Swiss chocolate, and even, at Christmas season, Beluga caviar. The store got its wish, at least for a while. The fashionable set came to West 34th Street. Even David Rockefeller stood in line to buy caviar. But Klein cut prices as well and managed through a clever and memorable publicity campaign to bring new customers into the store. In the heat of the Battle of the Beluga, the price of caviar was driven down relentlessly — to $120 from more than $200 for a 14-ounce tin. “We were handing over a $50 bill for each pound we sold,” says a former Macy’s employee.

While Klein kept a high profile on the cluttered floor of Zabar’s, Saul Zabar was rarely seen. That’s because he spent his days in Brooklyn, poking sides of salmon and slurping samples of black coffee and personally supervising the roasting of those that he chose. He still does it. Saul is legendarily finicky. He may reject all fish smoked in weather that’s too damp or too dry. Even when he’s accepted an order, he may reject it upon retasting it after it reaches Zabar’s. One supplier remembers seeing Saul so angry about a whitefish he’d just retasted after its arrival at the store that he threw it down and stamped on it.

Despite Saul’s demands, suppliers don’t walk away. It’s not only the store’s big buying power that keeps them coming back. It’s the firm’s practice of paying its bills in seven days — rare promptness that engenders great tolerance for whatever Saul wants. For years, Klein bought imported smoked fish while Saul handled domestic smokings. Unlike Saul, Klein expected the importer to check quality. Only when a customer complained about imported fish would Klein taste it himself. A few years ago, Saul complained to Klein that he wasn’t being attentive enough to quality. “Then you buy the fish,” Klein told his partner and walked away. Now Saul’s dominion over the fish counter is total. According to Klein’s suit, since Saul started managing the fish counter, “this business has declined substantially.”

Stanley Zabar has been least involved in the store over the years. David Liederman jokes that “he wouldn’t know the difference between a side of salmon and a gorilla.” That’s not really fair. It was Stanley who created the prepared-foods counter at the rear of the store 16 years ago. Saul wisely kept away. “If I’m looking over your shoulder, you won’t be able to do anything,” he told Stanley. From lemon-garlic chicken to lobster bisque, from soy-marinated loin of pork to giant barbecued shrimp, the counter generates about $6.5 million per year in revenue. Murray Klein, on principle, claims never to have tasted a single item from the department that Stanley created.

Real estate is to Stanley what lox is to Saul — his passion. He’s bought property up and down Broadway, both for the partnership and independently: apartment buildings, a parking garage, commercial buildings such as the one leased to Kiddie City at 79th Street. In the late ’60s, Stanley acquired the site of the former Schrafft’s restaurant two blocks north of the current store. With the popularity of Zabar’s already on the rise, the store urgently needed larger quarters. But, as usual, the partners couldn’t agree on how to make the move. The entire block front is now under renovation, about to become prime retail space that Zabar’s controls. Zabar’s itself has stayed put, expanding as adjoining stores become available. Even that’s been stormy. The former restaurant just to the north of Zabar’s was used for storage for five years after Zabar’s bought it because the partners could not agree on how to enlarge the store. In 1990, it finally became home to Zabar’s more than 50 varieties of bread, ranging from traditional bialys made by Kossar’s bakery on the Lower East Side to vanguard sourdough-cheddar rolls made by Soutine on the Upper West Side.

Like most unique institutions, Zabar’s is hard to analyze. When Sam Cohen, 40 years a fish cutter, says to a pretty young customer, “Come, let me help you, mein tchotchkela,” you know this store’s roots go deep. But half the countermen are now Chinese. And Zabar’s has always flouted Jewish tradition by being open on Rosh Hashanah and even Yom Kippur. It’s thought of as a chic store. Yet the displays are helter-skelter, and the old-time design of the Zabar’s shopping bag (1.5 million go out the door each year) hasn’t been changed since it was introduced in the ’50s.

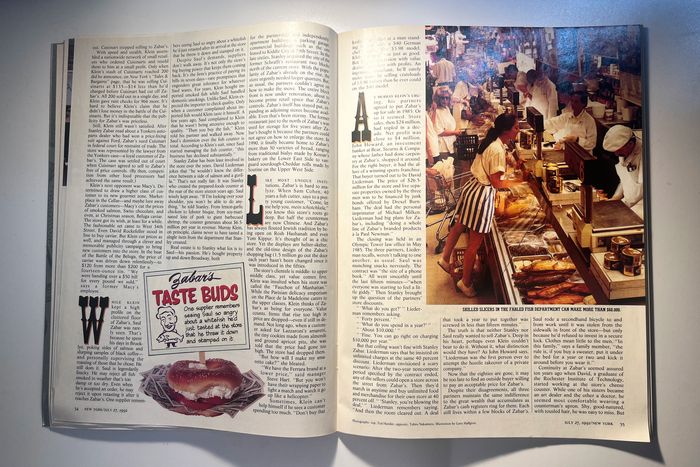

The store’s clientele is middle- to upper-middle class, Klein was insulted when his store was called the “Fauchon of Manhattan.” While the Parisian delicacy emporium on the Place de la Madeleine caters to the upper classes, Klein thinks of Zabar’s as being for everyone. Value counts. Items that rise too high in price are dropped — even if still in demand. Not long ago, when a customer asked for Lazzaroni’s amaretti, the tiny cookies made from almonds and ground apricot pits, she was told that the price had gone too high. The store had dropped them.

“But how will I make my amaretto cake?” she bleated.

“We have the Ferrara brand at a lower price,” said manager Steve Hart. “But you won’t have their wrapping paper to light a match and watch it go up like a helicopter.”

Sometimes, Klein can’t help himself if he sees a customer spending too much. “Don’t buy that knife,” he yelled at a man standing in line with a $40 German chef’s knife.The $3.98 model, Klein insisted, was just as good. But Klein’s obsession with value doesn’t interfere with profits. An ingenious merchant, he’ll surely make more by selling crateloads of $3.98 knives than he ever could on the $40 model.

At Murray Klein’s urging, his partners agreed to put Zabar’s up for sale in 1985. Or so it seemed. Store sales, then $24 million, had tripled in a decade. Net profit was close to $4 million. John Howard, an investment banker at Bear, Stearns & Company whose father had done carpentry at Zabar’s, shopped it around. For the right buyer, it had the allure of a winning sports franchise. That buyer turned out to be David Liederman. The price of $26.5 million for the store and five separate properties owned by the three men was to be financed by junk bonds offered by Drexel Burnham. The deal had the personal imprimatur of Michael Milken. Liederman had big plans for Zabar’s, including “doing a whole line of Zabar’s branded products à la Paul Newman.”

The closing was held in an Olympic Tower law office in May 1985. The three partners, Liederman recalls, weren’t talking to one another, as usual. Saul was munching snacks nervously. The contract was “the size of a phone book.” All went smoothly until the last 15 minutes — “when everyone was starting to feel a little giddy.” Then Stanley brought up the question of the partners’ store discounts.

“ ‘What do you get?’ “ Liederman remembers asking.

“ ‘Forty percent.’ ’’

“ ‘What do you spend in a year?’ ’’

“ ‘About $10,000.’ ”

“ ‘Fine. You can go right on charging $10,000 per year.’”

But that ceiling wasn’t fine with Stanley Zabar. Liederman says that he insisted on unlimited charges at the same 40 percent discount. Liederman envisioned a scary scenario: After the two-year noncompete period specified by the contract ended, any of the sellers could open a store across the street from Zabar’s. Then they’d march in anytime and buy unlimited food and merchandise for their own store at 40 percent off. “‘Stanley, you’re blowing the deal.’” Liederman remembers saying. “And then the room cleared out. A deal that took a year to put together was screwed in less than 15 minutes.”

The truth is that neither Stanley nor Saul really wanted to sell Zabar’s. Deep in his heart, perhaps even Klein couldn’t bear to do it. Without it, what distinction would they have? As John Howard says, “Liederman was the first person ever to attempt the hostile takeover of a private company.”

Now that the ’80s are gone, it may be too late to find an outside buyer willing to pay an acceptable price for Zabar’s.

Despite their disagreements, all three maintain the same indifference to the great wealth that accumulates as Zabar’s cash registers ring for them. Each still lives within a few blocks of Zabar’s. Saul rode a secondhand bicycle to and from work until it was stolen from the sidewalk in front of the store — but only because he’d refused to invest in a secure lock. Clothes mean little to the men. “In this family,” says a family member, “the rule is, if you buy a sweater, put it under the bed for a year or two and kick it around before you wear it.”

Continuity at Zabar’s seemed assured ten years ago when David, a graduate of the Rochester Institute of Technology, started working at the store’s cheese counter. While one of his sisters became an art dealer and the other a doctor, he seemed most comfortable in a counterman’s apron. Shy, good-natured, with tousled hair, he was easy to miss. But he did represent the family’s future. Eight years ago, Saul took on his nephew as an apprentice in the fish and coffee business. “It was like learning the violin from the greatest master in the world,” says Tracey Zabar. But great masters aren’t known for being easy on their students. Last January, David took off his apron for the last time.

Photo: New York Magazine

“My husband was supposed to be 80 years old and die in the store,” says Tracey. “But he was working so hard it looked like he’d have a heart attack at 40.” Long hours in the store wasn’t the problem. Neither was working on all major holidays. What did grind David down was predawn calls and visits to the smoked-fish houses, which traditionally open at 4 a.m. He was working at least 60 hours a week. A more driven man might have kept it up. But not David.

“I know a store on the East Side where the owners decided to stop working so hard,” he says. “One of them was from the old school. He thought you had to do it. But once they worked a normal workweek, instead of killing themselves, they discovered the quality of their work improved.” Saul Zabar is resolutely old school. He forced his nephew out rather than compromise over working hours. But he apparently thought better of it once David left. He wrote his nephew a letter asking him to come back — to no avail.

David Zabar left behind one revolutionary change — formerly impatient customers call it a stroke of genius — at Zabar’s: five cold cases filled with prepackaged foods, prepared on the premises, for which customers once had no choice except to “take a number.” To choose items at both the fish and meat counters, they had to take two numbers. On a Sunday morning, it was standard practice to read the Times while waiting — all of it. In a store where personal service counts, the change to prepackaged foods was momentous. “We did it because customers coming in at 6:45 on a weekday evening to pick up dinner have no time to wait — not if they want it on the table at 7:30,” says David. “But if you have the time, the man will still cut lox for you just the way you like it.” One-third of Zabar’s fresh foods are now sold prepackaged.

All Zabar’s top managers work grueling hours — 60 a week is normal. They’re paid well— six-figure salaries, profit sharing, and company cars. But there’s little time to use them. Scott Goldshine, one of the three front-of-the-store managers, once took off on a Saturday to go to a wedding. Klein never let him forget it. “My own wedding will be in the store.” says Goldshine. Steve Hart, the manager whose knowledge of the store is second only to Klein’s, actually married a former Zabar’s cashier.

Klein insists that employees show for work “unless they’re dead.” But he doesn’t call them at home. Saul does it regularly — at all hours. Tracey Zabar remembers getting an early-morning call from Saul at the store on a “priority only” home phone line when she was in the late stages of a difficult pregnancy. “The potato salad,” said Saul.

“What about the potato salad?” Tracey asked in a haze.

“It doesn’t taste right.”

False alarm. Saul had tasted an experimental batch of potato salad whipped up by David. The regular stuff had been prepared in bulk.

No single item is more closely identified with Zabar’s than smoked salmon. In a holiday the store can sell $300,000 worth. But surprisingly, it’s not a profit center. Bought for $10.50 a pound, it’s sliced to order at $19.95 per pound. But one-third is skin, bones, and end pieces. And the cutting, as David Zabar points out, is done “by old-world labor paid for at very modern wages. Senior countermen make more than $60,000 per year. The result is little or no profit on hand-cut-salmon sales. Precut-and-prepackaged fish — now representing half of Zabar’s sales does fetch a more normal profit margin.

Can one be too fanatic about quality? Tracey answers dryly, “This isn’t brain surgery, it’s fish.” In Saul’s hands, it may as well be brain surgery — or, the way his slender fingers knowingly dance over a fish, chiropractic. On a recent Thursday morning, he personally tasted through a $17,000 order of Pinneys Scottish smoked salmon. Tasting with him was the manufacturer’s agent, Kim Bruhn. Saul prefers wild salmon to the aquafarmed variety for their intense flavor — and he prefers those caught on hook and line rather than netted. “Sometimes they thrash for a long time in the nets and lose their fat,” he says.

Photo: New York Magazine

Poking, sniffing, munching, and spitting, Saul finds some of Bruhn’s fish taste “round and smooth,” some fine in the middle of the side but too salty at each end, others “at the edge of acceptability.” Last to be tasted are large sides of salmon farmed in Scotland but smoked by another supplier, in London. They’re known for fine smoking in London, says Bruhn. But not this time. Saul is displeased just from tapping his fingers along the skin side of the salmon. “Too hard, too rubbery.” He finds that the fish has been cut “sloppily.” Worst of all, it tastes “raw, like sushi.”

Eyes often roll at Saul’s obsessiveness. This time, Bruhn is with him. She agrees to take back hundreds of dollars’ worth of London smoked salmon without a murmur. Somebody will eat it, perhaps even praise it, but not customers of Zabar’s.

Like true love, Murray Klein’s anger at his partners does not fade with age. “If Saul Zabar walks in that door.” said Klein one afternoon, “I walk straight to the other side of the store.” But he does it with a flourish. When Saul walks into the store the next morning. Klein abruptly stops adjusting a stack of electric juicers in the window.

“I’m going up to my office to read the Times,” he says in a voice loud enough to get him a job in the legitimate theater.

“Again?” asks a cashier. “You already read the Times this morning.”

But Klein would rather read the Times twice than look at his partner once.

“They act like two children,” mutters the cashier. But what’s going on at Zabar’s isn’t child’s play. As the partners feud and grow old, it’s the store that may be the loser. Who will replace Klein? How will customers be assured of Olympian smoked-fish standards when Saul stops tasting? Can Zabar’s still be the “most rambunctious and chaotic of all delicatessens”? Not necessarily. And certainly not while the partners line up behind their lawyers.

Time grows short. Saul says. “We’re all feeling the Grim Reaper breathing on us.” If Zabar’s ever becomes a shadow of itself, it will be like when the Dodgers left Brooklyn. The Upper West Side will be left with an ache that won’t go away.